GW’s Blood & Bone Marrow Transplant Program Is the One Best Option for Area Patients in Need

A little more than two decades ago, The George Washington University was seeking to re-establish a bone marrow transplant (BMT) program. Many at the University, including Robert Siegel, M.D., professor of medicine at GW’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS), and chief of the Division of Hematology/Oncology at the GW Medical Faculty Associates, believed that having a viable BMT program “was central to maintaining our credibility as a tertiary care center for the treatment of cancer,” in Siegel’s words.

GW had high aspirations for the program and set its sights on a Lebanese-born, 30-something physician at the University of Virginia (UVA). Imad Tabbara, M.D., earned his undergraduate and medical degrees from the American University of Beirut. He completed his fellowship training in hematology/oncology at UVA and was quickly appointed an assistant professor of medicine at the school. For GW, he was “the One.”

Tabbara arrived in Foggy Bottom in 1992 and immediately set about forming a lab and team of nurses, pathologists, and pulmonary and infectious disease specialists. Employing a sunny personality and a steely resolve, Tabbara, who now serves as professor of medicine at SMHS and director of the Blood & Bone Marrow Transplant Program, won over those who doubted the efficacy of a BMT program. In the 20 years since then, GW’s program has performed close to 1,000 transplants, growing from two or three per year to between 30 and 50 annually, and boasting a low 3 percent mortality rate.

Though GW’s BMT program is relatively small — Seattle’s Hutchinson Center performs more than 200 transplants a year, the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston does 200 annually, and New York’s Sloane-Kettering about 150 — it’s the only game in town in Washington, D.C., and aspires to grow bigger and better.

“We are the size of other university programs,” says Tabbara. “We draw from D.C., Northern Virginia, and Maryland. In Virginia, the only other program is the Medical College of Richmond, which is two hours away.”

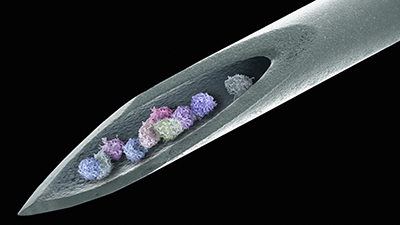

By their nature, BMT programs can be a tough sell. With marrow transplants, unlike many other therapies, patients have to be made very sick before they can be made better. Before the transplant, the patient receives ablative treatment; high-dose chemotherapy, radiation, or both are given to kill any cancer cells. This also kills all remaining healthy bone marrow, to allow new stem cells to grow. A stem cell transplant is done after chemotherapy and radiation is complete. The stem cells are delivered into the bloodstream usually through a tube called a central venous catheter, and they travel through the blood into the bone marrow.

Tabbara speaks of his successful transplants like a proud parent. His first BMT at GW, in May 1992, was a 28-year-old pastry chef in the District suffering from acute leukemia. Twenty years later “she’s alive and healthy and completely fine.” Another woman with acute leukemia didn’t have a donor “but I harvested her stem cells when she was in remission, and she’s now 15 years out and has had two children,” says Tabbara. “Her sister-in-law is a nurse on my team.”

A major impediment to the program’s growth, according to Tabarra, is negotiating contracts with insurance companies. Siegel adds that insurers look for larger BMT programs. “We have a chicken-and-egg situation here,” he says. “If we can build the volume, we can attract the insurers. I’d like to go to 70–100 transplants annually, then we can hire more people and apply to be a member of the International Bone Marrow registry.”