Tucked in an unassuming office in the George Washington University (GW) Ross Hall, David Diemert, MD, has a running list of thousands of healthy people who have volunteered to receive experimental vaccines. Some have friends or relatives with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and want to contribute to the quest for an HIV vaccine. Others are willing to be infected with hookworm to test the effectiveness of a new vaccine. Many signed up early on during the COVID-19 pandemic, eager to speed up the advent of a COVID vaccine.

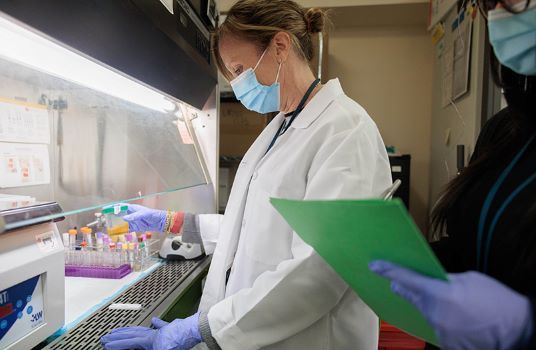

At any given time, hundreds of these people are actively participating in about a dozen vaccine clinical trials run by the GW School of Medicine and Health Science’s Vaccine Research Unit (VRU). In a span of less than five years, the VRU has become one of the leading sites in the country for vaccine clinical trials.

“It’s taken a lot of hard work to establish the VRU, but it’s paid off; we’re starting to make a name for ourselves,” says Diemert, the unit’s clinical director as well as a professor of medicine and of microbiology, immunology, and tropical medicine.

Inspired by Neglected Diseases

Diemert, along with colleague Jeffrey Bethony, PhD, who heads up the VRU’s Clinical Immunology Lab, came to GW in the early 2000s to develop and test hookworm vaccines. Both had conducted years of field research on vaccines — Diemert in West Africa and Bethony in Thailand — and were motivated by the pressing need to prevent diseases such as malaria, hookworm, and schistosomiasis that were rampant in the developing world.

Armed with a large grant from the Gates Foundation, Bethony and Diemert began building from scratch a facility and the expertise to evaluate new hookworm vaccines. Unlike drugs for diseases such as cancer, which are often tested first in the sickest patients, vaccines are designed for healthy people — and tested on healthy people. That complicates the recruitment of participants and translates to a lower tolerance for side effects. It also means the infrastructure for vaccine trials is very different than that for other drugs.

In the United States, experimental vaccine studies are typically only carried out at a handful of large centers that have expertise in how to safely plan, carry out, and analyze these studies. At the dawn of the millennium, GW wasn’t one of these centers.

“At the same time we were developing hookworm vaccines, we were also developing our own skills as researchers and developing the infrastructure at GW for vaccine testing,” says Bethony, who also serves as professor of microbiology, immunology, and tropical medicine at SMHS. “We learned, from soup to nuts, how to put together a vaccine research unit.”

A Bigger Portfolio

By 2018, Bethony, Diemert, and their colleagues had been successful in moving an early-stage hookworm vaccine through initial clinical trials in Brazil and enrolling their first group of healthy volunteers at GW. But they were then approached about another opportunity: the chance to become one of the first sites in the world to test a new generation of HIV vaccine. Diemert and Bethony signed on, and decided their efforts needed a more formal name. The VRU was born.

“It was really a purposeful, philosophical decision that if we wanted to be a prolific, high-quality vaccine testing center, we had to expand beyond neglected tropical diseases,” says Diemert.

At the same time, they expanded the staff of the VRU to support the new clinical trials. Elissa Malkin, DO, MPH, who had studied malaria in Malawi and, more recently, directed vaccine development at AstraZeneca, joined the VRU. A regulatory team helped ensure that trials followed proper protocols and a data management group was formed.

“We’ve been lucky to accrue a really fantastic group of people who are all focused on getting things done right and delivering high-quality data,” says Malkin, an assistant research professor of medicine at SMHS.

Last December, the results of that first HIV vaccine study were published in the journal Science and the VRU’s role was key. Researchers had designed the vaccine to spur the body’s production of a rare type of immune cell nestled deep inside the lymph nodes. Bethony and his team at the clinical immunology lab crafted new methods for collecting those cells from the pea-sized lymph nodes of healthy volunteers — a much harder task than harvesting cells from the large, swollen lymph nodes of cancer or tuberculosis patients.

“This technique that we developed turned out to be absolutely critical for studying the vaccine,” says Bethony. “You can draw a tube of blood and not find any of these immune cells, but we showed that they’re present inside lymph nodes.”

Pandemic Expansion

The timing of the VRU’s establishment and shift toward HIV studies turned out to be auspicious; in 2020, the federal effort for a COVID-19 vaccine turned to the HIV Vaccine Trials Network for help selecting sites for the leading vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. In a matter of months, the VRU enrolled nearly 400 volunteers in a Phase III trial of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. In 2021, they were then asked to help run a Phase II/III trial of the Sanofi vaccine.

“It wouldn’t have been possible to accomplish this if the VRU wasn’t already familiar with how to work a vaccine trial, and extremely adept at everything from budgeting to logistics and having the right personnel and lab space,” says Marc Siegel, MD, associate professor medicine at SMHS and director of the division of infectious diseases.

The VRU not only met its enrollment goals in the COVID-19 trials, but also showed the nation’s vaccine research community just how smoothly the research team could conduct a trial, and how willing the D.C. community was to participate.

“One thing that is good about D.C. is we get a very diverse population to test vaccines,” says Bethony. “We also don’t have the same levels of vaccine hesitancy that you see in some other parts of the country.”

Knocking at the VRU door

In the months since publishing its first HIV vaccine results and participating in the COVID-19 trials, the VRU has gotten a deluge of requests to help out with more trials, studying vaccines against diseases from shingles to monkeypox.

“Once you open the tap, if you have a good reputation and you’re not reckless, you start getting a flood of people coming to you,” says Diemert. “We have organizations and pharmaceutical companies approaching us now and asking if we’ll conduct their trials.”

The team doesn’t jump at every opportunity, however. For initial trials of vaccines that have never been in people before, the VRU wants to do things right and maintain its reputation. The unit carefully analyzes data on a potential vaccine— as well as details on how a company or organization was to run any trial — before agreeing to participate.

“With Phase I vaccine trials, you don’t want to be a cowboy; you want to do rigorous, safe science,” says Bethony. “The potential to make healthy people sick is a big burden, and we don’t take on trials that we feel are unnecessarily risky.”

There are still only 10 official Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units (VTEUs) in the United States sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, and the VRU doesn’t yet belong to this exclusive list. Gaining this funding — which comes with opportunities to run vaccine trials only evaluated through VTEUs— is a long and competitive process. Diemert says he hopes to apply soon.

In the meantime, the VRU has trials at all stages of completion, including COVID-19 booster vaccine trials as well as continued work on neglected tropical diseases. Recently, the researchers gave volunteers three different formulations of their hookworm vaccine — each with a different adjuvant, a compound designed to boost the vaccine’s effectiveness. Then, volunteers were challenged with hookworm to see if the vaccine prevents the infection taking hold. The results, the team says, are coming soon.

The VRU also runs clinical trials at field sites around the world; recently launching a trial in Uganda for a vaccine against schistosomiasis, a disease caused by flatworms that infects hundreds of millions of people in Africa, Asia, and South America each year.

Malkin, who came to the VRU from industry, says it’s a vibrant and active place to work. The staff, she says, share a belief in the power of vaccination.

“Vaccines are one of the most important public health prevention tools that have ever been developed and I think we all agree that to be able to work on them every day is a privilege,” she says.