Kris Lehnhardt was lying on the living room floor of his Toronto home, watching TV with his mother, when the original Star Trek TV show came on. He stared, enraptured, a small boy trying to comprehend life exploring the universe. A few years later, his second grade class huddled around a television as a NASA space shuttle launched into orbit. Tears streamed down his cheeks. The tension, the adventure ...

You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure out this trajectory.

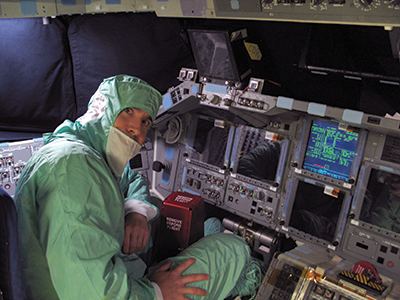

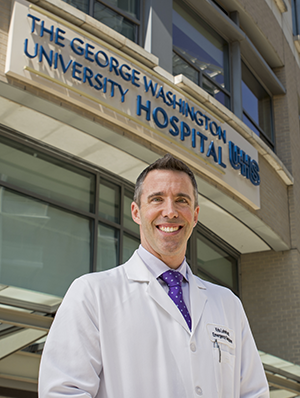

Kris Lehnhardt, M.D., never let go of his dream to boldly go where no one has gone before. An aspiring astronaut, he is an assistant professor of emergency medicine and medical director of EMeRG (George Washington University Emergency Medical Response Group), and he teaches a popular course on campus, aerospace medicine. In addition to being an expert in space medicine and the discipline known as extreme environmental medicine, Lehnhardt is a certified pilot, an advanced open water SCUBA diver, a reservist in the Royal Canadian Air Force, and an avid traveler. He also served as the flight surgeon for the Mars Desert Research Station until 2015.

In short, “Dr. Space” has done everything possible to make himself a superior candidate for that special group of people who yearn to sit atop a gigantic Roman candle and be hurled into zero gravity. Everything — even changing his nationality, sort of. “ I have a green card and I will be applying for dual citizenship as soon as possible,” he says. Lehnhardt was one of 5,500 applicants to the Canadian Space Agency in 2008 and qualified for the final 200. Candidates selected: two. Conclusion: Improve your odds. So Lehnhardt moved to the United States “because I thought my aerospace medicine skills would be key,” he says. Washington, D.C. is where space policy is born, and GW was receptive to encouraging space medicine. “All of what I do is potential steps toward my ultimate goal of becoming an astronaut,” he explains.

Lehnhardt’s wife, Emma, who works on strategic budget planning at NASA (where else?) says her husband is “very realistic” about his chances of reaching space. “I never find myself needing to provide checks and balances,” she says. “He knows it’s hard, not just to qualify, but there’s serendipity involved.” Scott Pace, Ph.D., a seasoned veteran of NASA and the White House who now directs the Space Policy Institute at GW’s Elliott School of International Affairs, consulted with Lehnhardt on his space medicine course, which provides a scholastic link for his own students. “On a space nerd scale, Kris is above average, but he’s pretty grounded,” Pace says. “If you run into somebody who really, really has to be an astronaut, people who are that obsessive are probably not the ones you want to place in a small metal canister and send into space!”

Part of Lehnhardt’s pathway to the stars is spent in Ross Hall’s room 104, where students gather to explore the effects of space travel on the human body. EHS 6227, Introduction to Human Health in Space, is open to med students, as well as GW graduate and undergraduate students. Class rosters run the gamut from medical residents to criminal justice majors and many future biomedical engineers. Lauren Ryan of East Greenwich, Rhode Island, who is pursuing a Ph.D. in bioastronautics and has already interned at NASA’s radiation labs through the National Space Biomedical Research Institute, was one of the first to take the course. “I learned a lot about spaceflight’s effect on the human body and how we can possibly counteract these effects,” she says. “I hope to work in this field one day, coming up with new medical technologies for human spaceflight.”

Then there was Zack Hester of Marion, South Carolina, a graduate student in International Science and Technology Policy at the Elliott School, who is interested in a career in space policy. “A foundational knowledge of the medical effects of spaceflight on the human body is important, as NASA plans to embark on new long-duration human spaceflight missions and commercial companies start to offer flights for tourism over the next decade,” he explains. That’s exactly what Lehnhardt hopes to impart to his students. “I want to outline the effects of space flight on human physiology and the medical issues that arise during space travel,” he tells them.

Space travel of any duration is tough on human anatomy: Muscles atrophy, zero gravity induces vertigo, eye problems can result from changes in intracranial pressure, bones become more brittle, and organs tend to shift in the body. Oh, and what about your mind: What is the effect on the human psyche when you can no longer see Earth or feel its pull?

“Aerospace medicine is a critical support function” for the space program, says Rich Williams, M.D., NASA’s chief medical officer, who advised Lehnhardt on his syllabus and who serves as a guest lecturer. Other extreme environments raise similar medical issues, Williams explains, but space medicine differs owing to two important exposure factors — “microgravity and the level of radiation exposure. Over the past 50 years of human spaceflight, space medicine has emerged to care for the astronaut and mitigate the effects and risks of spaceflight,” says Williams.

In addition to his work as the medical director of EMeRG, Lehnardt directs the Fellowship in Extreme Environmental Medicine, which offers emergency medicine physicians one year of training in wilderness, disaster, and other extreme medical environments.

Nearing 40, Lehnhardt has stayed focused on his goal of going into space but declares “as long as I’m doing things along the way that I enjoy, I worry less about the goal.”

Can a dreamer be a realist, too? Lehnhardt estimates he has “a few more years” of eligibility before his age becomes an insurmountable hurdle to joining the “right stuff” crew. Space medicine experts have no such limitations, however, and for Kris Lehnhardt, that may be just the ticket.