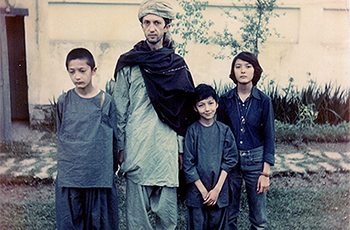

The family photo, faded and slightly worn, tells a story. The muted tones recall a sunny day in Kabul, before the family fled the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Leaving everything behind — money, possessions, privilege, and professions — the family escaped with 10 others in the back of a pickup truck. Dour faces stare into the camera, all except that of one boy, who smiles broadly without a hint of anxiety, as only a 6-year-old can.

“I’m the one with the goofy smile,” laughs Mohammad Ali Aziz-Sultan, MD ’99, who is now a lifetime away from the boy with the sunny disposition who stood in the Afghan capital as his homeland slid into decades of chaos and war. “I guess I thought it was some sort of game we were playing.” But it wasn’t a game.

The weeklong journey over rough and dusty roads into Pakistan ultimately would lead the family beyond borders, across continents, and over oceans. For Aziz-Sultan, the odyssey would lead to unimaginable success as a renowned neurosurgeon trained in both cerebrovascular and endovascular surgery and gifted in the high-stakes game of aneurysm repair and stroke care. Aziz-Sultan is the Chief of Vascular/Endovascular Neurosurgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an Associate Professor of Neurosurgery at Harvard Medical School. He is also the director of the microsurgical laboratory, and the co-director of the Comprehensive Stroke Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Those academic credentials flow directly from his George Washington University (GW) School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS) medical degree.

Arriving at this point, however, was a journey, not a jaunt. The memory of each roadblock or detour along the way serves to guide Aziz-Sultan back to his earliest desires for a life of medicine and healing. Led by his parents, who abandoned prominent careers as MD/PhD OB/GYNs, the family endured a succession of moves after fleeing to Pakistan. Aziz-Sultan; his older brother, Ajmal; and their parents traveled to Germany, where they lived in a cramped apartment. From there, a former colleague of Aziz-Sultan’s parents, John Haswell, MD, whom they had met years earlier at a medical conference, tracked the family down and sponsored them to come to the United States. They landed in Vincennes, Indiana, a rural farming community in the southwestern part of the state. It was a small, close-knit community when Aziz-Sultan arrived in the early 1980s, and, he jokes, the area was light on diversity.

“There was one African-American family and zero foreign families when we arrived,” Aziz-Sultan recalls. He adds that a family of central Asian refugees was a novelty, but the community was extraordinarily welcoming. “This three- to four-year period of my life … it was the most loving place. I never saw anything but love, appreciation, and support.”

When the family moved again, this time to Alexandria, Virginia, where employment opportunities were greater, Aziz-Sultan fell easily into the common pitfalls of suburban America. With his parents away from home for long hours working multiple jobs, he spent much of his free time “hanging out.” That lack of direction, and underwhelming undergraduate grades, stalled his medical school admissions efforts. Aziz-Sultan found himself on GW’s waiting list, wondering if his dream of being a doctor was over. He had one particularly poor semester. “I carried those grades with me in my back pocket,” he recalls. “I literally folded up that report card and carried it in my wallet. Any time that I thought about doing something that wasn’t focused on my final goal, I would reference it, as a reminder of the consequences of losing focus.”

What he needed was a window of opportunity, and it came in the form of an understanding admissions officer who chose to take Aziz-Sultan at his word. The SMHS dean of admissions at the time was John F. “Skip” Williams Jr., MD ’79, RESD ’83, MPH. “He took a chance on me,” recalls Aziz-Sultan. “I … told him that given the opportunity, I would not let him down.”

Impressed by his determination, Williams plucked the young Aziz-Sultan off the waiting list, opening the way to medical school. Once on campus, Aziz-Sultan began to reinvent himself. He loved medicine and being immersed in a community of talented, supportive students and faculty. He recalls rotating through different clinical settings and witnessing patients battling serious illnesses. “It wakes you up. You see yourself,” he says. He also realized that, by committing himself to medicine, he was committing himself to providing that same level of compassion and empathy he once received as a child refugee.

“Suddenly, it’s more than grades. It’s more than school. It’s literally like falling in love. You become infatuated and develop a sort of tunnel vision,” he says. “The heart is there, the mind is there, the purpose is there. It draws you in deeper and deeper.”

Given a second chance, Aziz-Sultan set his sights on the top. For him, that meant neurosurgery. He dedicated his time in medical school to achieving that goal. Postgraduate work featured a neurosurgical residency at the University of Miami, with endovascular fellowships in radiology and neurologic surgery, and a fellowship in skull-based and cerebrovascular surgery at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Arizona.

At that time, microsurgery was in its heyday. The specialty was revolutionized in the late 1960s with the invention of the surgical microscope, offering neurosurgeons a small window into the brain. Peering into a microscope, neurosurgeons could travel down the fissures between the lobes of the brain to find the affected vessels, where they could place a tiny clip over an aneurysm, a little bubble that forms on the vessels of the brain.

“[Surgically repairing aneurysms] took me seven years to learn,” Aziz-Sultan says. While he was honing those skills, the fields of radiology and endovascular surgery began to emerge. “People were starting to make real gains in the field in the mid-2000s … taking catheters through the femoral artery, just like the cardiologists.”

Guiding catheters into the brain, physicians could seek out aneurysms and place tiny coils in the vessel to stabilize the area. These new procedures enabled surgeons to do in an hour or two what once took 15 hours to accomplish. Every new technique or piece of equipment, however, encroached a little further on the microsurgical domain. As the endovascular field blossomed, a turf war erupted, pitting microsurgeons against endovascular surgeons, clips versus coils.

Aziz-Sultan, seven years into his training, decided that rather than join the microsurgical resistance and fight the endovascular revolution, he would instead study it.

“What do you do?” he asks. “Are you all this field or all that field? Or are you somebody who takes new ideas from different places and tries to incorporate them and come up with something even better? Innovation has to do with bringing together different thought processes. It has to do with diversity, diversity of background, diversity of gender, diversity of thought, diversity of everything.”

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Aziz-Sultan and his team paired tactics and techniques from radiology and neurosurgery with those of endovascular surgery to create an innovative, one-stop shop for stroke and aneurysm repair.

“We created a hybrid operating room where we can operate through a microscope and use biplane angiography at the same time, and [tackle] unique cases that weren’t possible before,” he says. “Innovation has nothing to do with holding on to what you have, and putting up walls because you’re a neurosurgeon and a radiologist is coming to take your job,” insists Aziz-Sultan. “It has to do with opening your mind and being malleable. That’s the most important thing that I’ve learned so far, and it’s the key to what has let me thrive in my specialty. I learned these principles by my life circumstances, as a refugee kid from Afghanistan.”